Because data centers and telecom switching centers are designed to withstand failures without interrupting business operations, a 3 a.m. emergency due to a malfunctioning air conditioner should never occur – in theory. But Murphy’s Law says that if a single failure can create an emergency, it will. So, to date, operators have had to react to single-component failures as if they are business-critical. Because they might be.

In my previous blog, I pointed out the two components of risk: the probability of and the consequence of failure. While both of these components are important in failure analysis, it is the consequence of failure that’s most effective at helping decision-makers manage the cost of failure.

If you know there is a high probability of impending failure, but you don’t know the potential consequence, you have to act as though every threat has the potential for an expensive business interruption. Taking such actions is typically expensive. But if you know the consequence, even without knowing the probability of failure, you can react to inconsequential failures at your leisure and plan so that consequential failures are less likely.

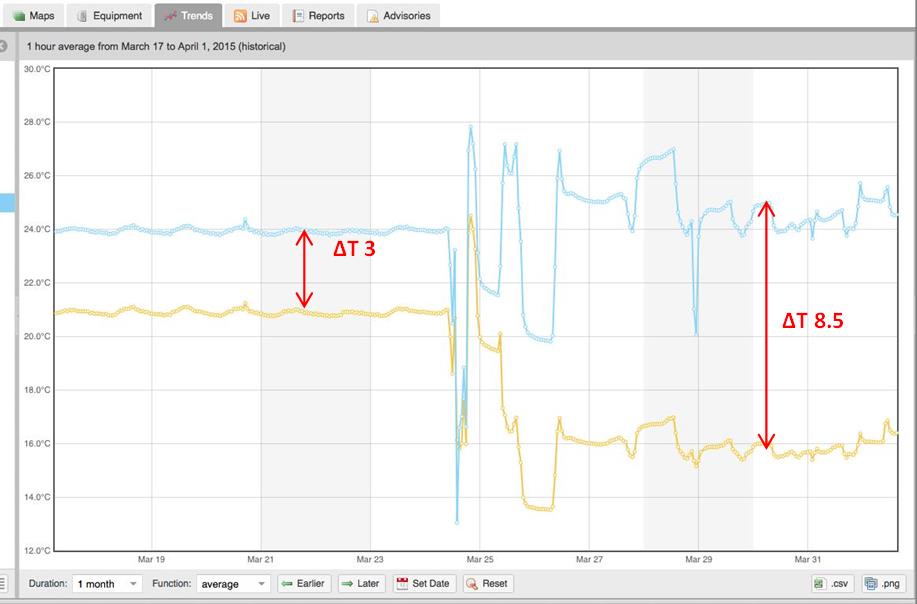

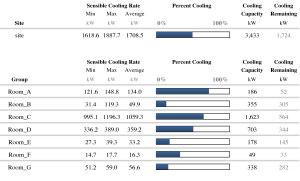

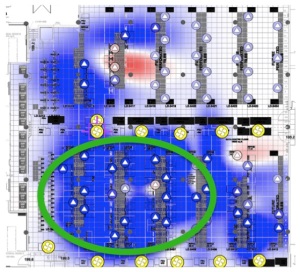

In the past, the consequences of a failure weren’t knowable or predictable. The combination of Internet of Things (IoT) data and machine learning has changed all that. It’s now possible to predict the consequence of failure by analyzing large quantities of historical sensor data. These predictions can be performed on demand and without the need for geometrical data hall descriptions.

The advantage of machine learning-based systems is that predictive models are continually tuned to actual operating conditions. Even as things change and scale over time, the model remains accurate without manual intervention. The consequences of actions, in addition to equipment failures, become knowable and predictable.

This type of consequence analysis is particularly important for organizations that have a run-to-failure policy for mechanical equipment. Run-to-failure is common in organizations with severe capital constraints, but it only works, and avoids business interruptions, if the consequence of the next failure is predictable.

Predicting the consequence of failure allows an operations team to avoid over-reacting to failures that do not affect business continuity. Rather than dispatching a technician in the middle of the night, an operations team can address a predicted failure with minimal or no consequence during its next scheduled maintenance. If consequence analysis indicates that a cooling unit failure may put more significant assets at risk, the ability to predict how much time is available before a critical temperature is reached provides time for graceful shutdown – and mitigation.

Preventative maintenance carries risk, but equipment still needs to be shut off at times for maintenance. Will it cause a problem? Predictive consequence analysis can provide the answer. If there’s an issue with shutting off a particular unit, you can know in advance and provide spot cooling to mitigate the risks.

The ability to predict the consequences of failure, or intentional action such as preventative maintenance, gives facility managers greater control over the reliability of their facilities, and the peace of mind that their operations are as safe as possible.